CloudCar – In-car computing platform

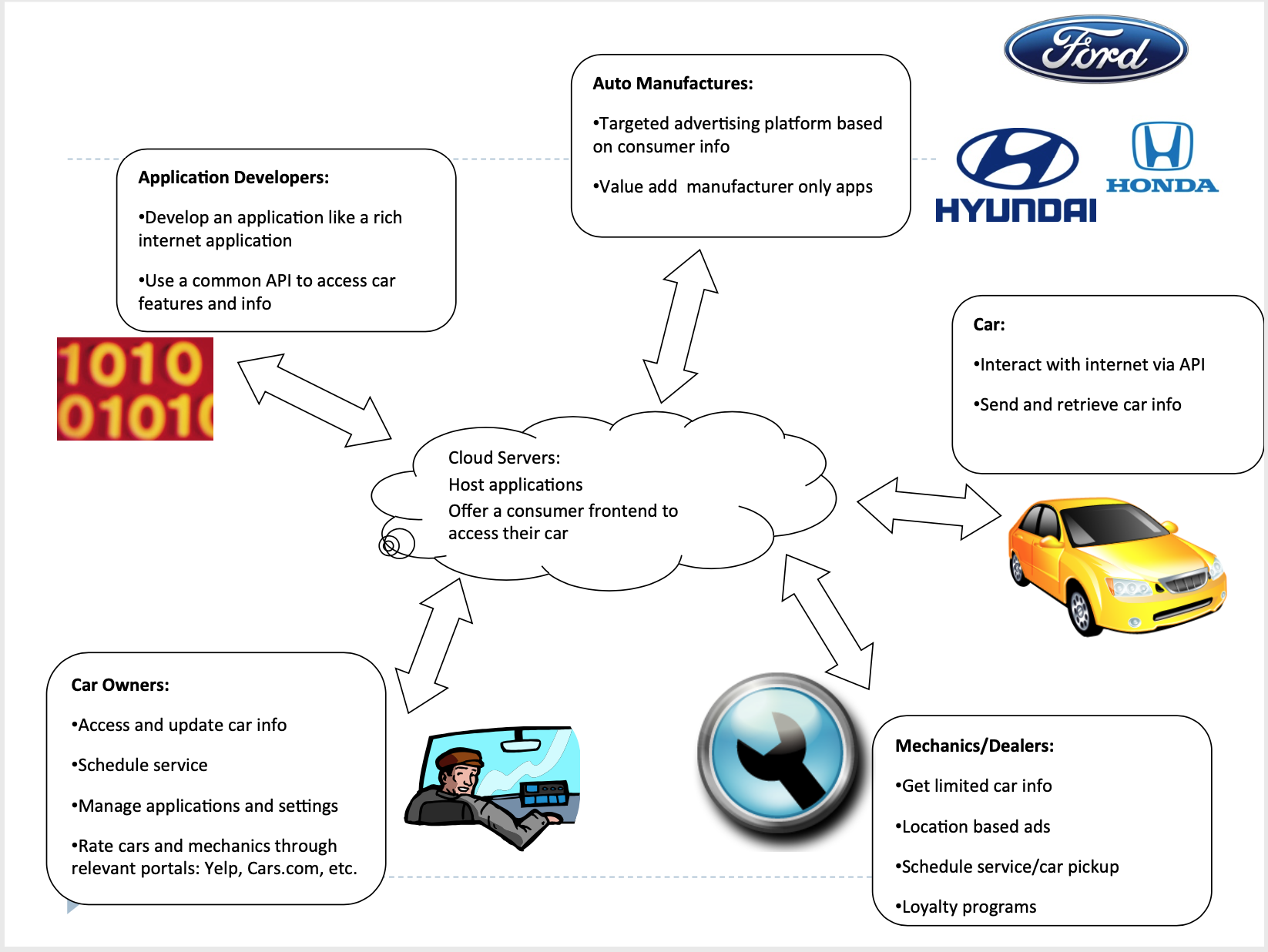

A platform to unleash the data locked inside our cars to application developers, and improve in-car technologies.

Since I was a young child, I’ve loved cars. They’re so mechanical, made up of so many carefully coordinated subsystems, and yet so efficient. They can move you from place to place, in a climate controlled environment, with your choice of entertainment, comfortably at 80 mph, using just gallons of fuel. There’s millions of them built annually, at low costs. That’s amazing.

I’ve also loved computers since I was a child. How does a machine that’s so tremendously complicated work? How is it that a computer can play music, send emails, do math, and show graphics, when almost every other device is single purpose? How can typing something with your keyboard control exactly what a bunch of devices in a box do?

Then I began to consider the intersection of these two amazing pieces of engineering. I was fascinated by the emergence of mobile computing since the days of Windows Mobile, and mobile computing was only accelerating with the proliferation of iPhone and Android. These platforms took data that was formerly locked away in closed platforms – contact information, location, email - and unleashed it on a platform with an internet connection to developers.

I was already starting to see the potential for in-car computing through these devices – not only navigation, but communication, home automation, and even car diagnostics and maintenance. (see: MITE46) But mobile devices were ill suited to use in the car – their UI/UX didn’t suit cars and they didn’t integrate with the systems already in the car. There were already significant in car computers collecting engine data and managing the car entertainment and convenience functions. But this data was locked away. I envisioned a platform that would unlock this data, and unleash it to the internet, for developers to creatively use.

Hobbyists were headed in this direction already. Their work primarily grew out of their desire in the early 2000’s to play MP3s in their car, without any media (discs). In their earliest solutions, a laptop or compact computer was installed in the glove box or under the seat, and a touchscreen monitor was installed in a 2-DIN radio slot. The car amplifier was retained, or if the radio that was removed had an amplifier, then an external one was installed as space allowed. Custom software optimized for touch and in-car use was installed – RideRunner, openMobile, and LinuxICE are popular choices. These software managed music and settings, and often had a ‘plug-in’ system for additional apps – from navigation to OBDII to fuel prices. Custom hardware had to be installed for power management - automatic startup and shutdown.

These solutions represented the first generation of thinking about the solution. With off the shelf hardware and basic community developed software, they were far ahead of their time, but their imperfections were obvious. The interfaces were clunky and slow, the software was unreliable, the hardware was expensive and often required custom fabrication. The software was only usable by enthusiasts willing to tinker. There have been incremental improvements ever since – faster, smaller, and easier to use hardware, improved software, newer HMI, and more.

The next generation of solutions involved mobile devices. People began installing iPads and Android tablets in their car as soon as they were available. These devices, because they were built from the ground up with mobile in mind, were small, light, cheap, low power, and had excellent connectivity – 3G/4G, Bluetooth, WiFi, and GPS were all quite common. The software was fast, stable, touch centric, and importantly, cloud first. Even though these devices were far better, they weren’t compatible with the car’s legacy systems. They worked dis-jointly. And they still required a hobbyist to install the device into the car permanently.

Summarized – the key problems with in-car technology:

• Development lifecycle. A car may take 5 years to develop, but software can have a lifecycle of months, and a web app can have one of days. A car can easily last 10 or more years; a piece of technology is easily outdated annually. Automakers were taking their technology systems through the same development cycle as their cars.

• Open vs. closed platforms. Automakers have a culture of ‘doing things their way.’ Technology has exactly the opposite expectation. The power and popularity of a computing platform has a lot to do with it’s openness – the iPhone became tremendously more useful and popular with the advent of the app store. Automakers have a very difficult time embracing this concept.

• Integration with existing systems. All new systems are rare. Even mobile devices and OSes have to work with legacy systems – email, MP3, calendar, PDF, and web browsing, to name a few. If the new platform can hook into the car’s existing systems – like OBD data – then developers will undoubtedly come up with creative applications.

• Low power on off – Automotive applications are particularly sensitive to power draw when off. You can’t run a computer when the car is off because it will drain the battery quickly. So if you’re going to provide some kind of always on connectivity, then it must draw power very sparingly, even less than a cell phone.

My solution to these problems was CloudCar – a web-based in-car computing platform. Develop apps like you would a web app – with HTML5, JavaScript, CSS, and jQuery. Accessing system resources, services, and data via CloudCar’s JS library – in a standard format for every car. Distribute your apps on the app store – and update them as frequently as you’d like. Voila.

The hardware is equally innovative. The whole system is essentially a tablet. The car’s hardware is entirely swappable by replacing the unit. The device is connected to the car with a simple set of pins – power, OBD bus, and automotive Ethernet (successor to CAN bus). The device is user-replaceable, in case of repair or upgrade.

We would develop a reference implementation for automakers to modify in their own implementation. We’d charge automakers a nominal fee of $30/car for the use of the technology stack – not including the hardware itself. They’d be willing to pay this because it would save them substantial software and engineering resources. We’d provide the updates for software, and our hardware partners would actually manufacture our reference implementation hardware. We’d further make money from selling ads based on data mining of users’ preferences, requirements, and habits.

If you’d like to see more about my work on this project, please check out the attached media.