RR2P150 Transfer Line, Fermilab

Developed a new transfer line to enable Femilab’s Main Injector take on a new era of research.

Meiqin Xiao’s Presentation (pdf)

The summer after my sophomore year at IMSA, I got the opportunity to intern at Fermilab, in Batavia, IL – quite close to my home and school. This was exciting not only because I got to work at Fermilab, but because I got my drivers’ license the first day after school ended, and I was going to commute every day in my car.

My mentor Dr. Meiqin Xiao worked in the Main Injector/Recycler Ring department. This was my first experience working outside of school. I arrived and got my Fermilab laptop. All the systems at Fermilab were Linux. At this time, I didn’t really know how to program or how to use the Linux terminal, other than very basic commands – ls, cd, pwd, cp. I didn’t know how to use text editors like vim or even nano from the command line.

I met my mentor one week before my work started. She gave me a book called (Particle Accelerator Physics Part I: Basic Principles and Linear Beam Dynamics)[http://www.amazon.com/Particle-Accelerator-Physics-Principles-Higher-Order/dp/3540006729] so I could learn a little bit before the start of the internship. I remember it distinctly because when I got home, I looked on the inside cover and there was a Post-it note that said, “Please distribute to all the post-docs in the department.” It was at that point I realized I might be out of my depth. I was a high school student who had just studied basic mechanics, at the world’s premiere lab for particle physics. I spent a week learning about the basics of electricity and magnetism, and vaguely understanding the relationships between B fields, E fields, and forces.

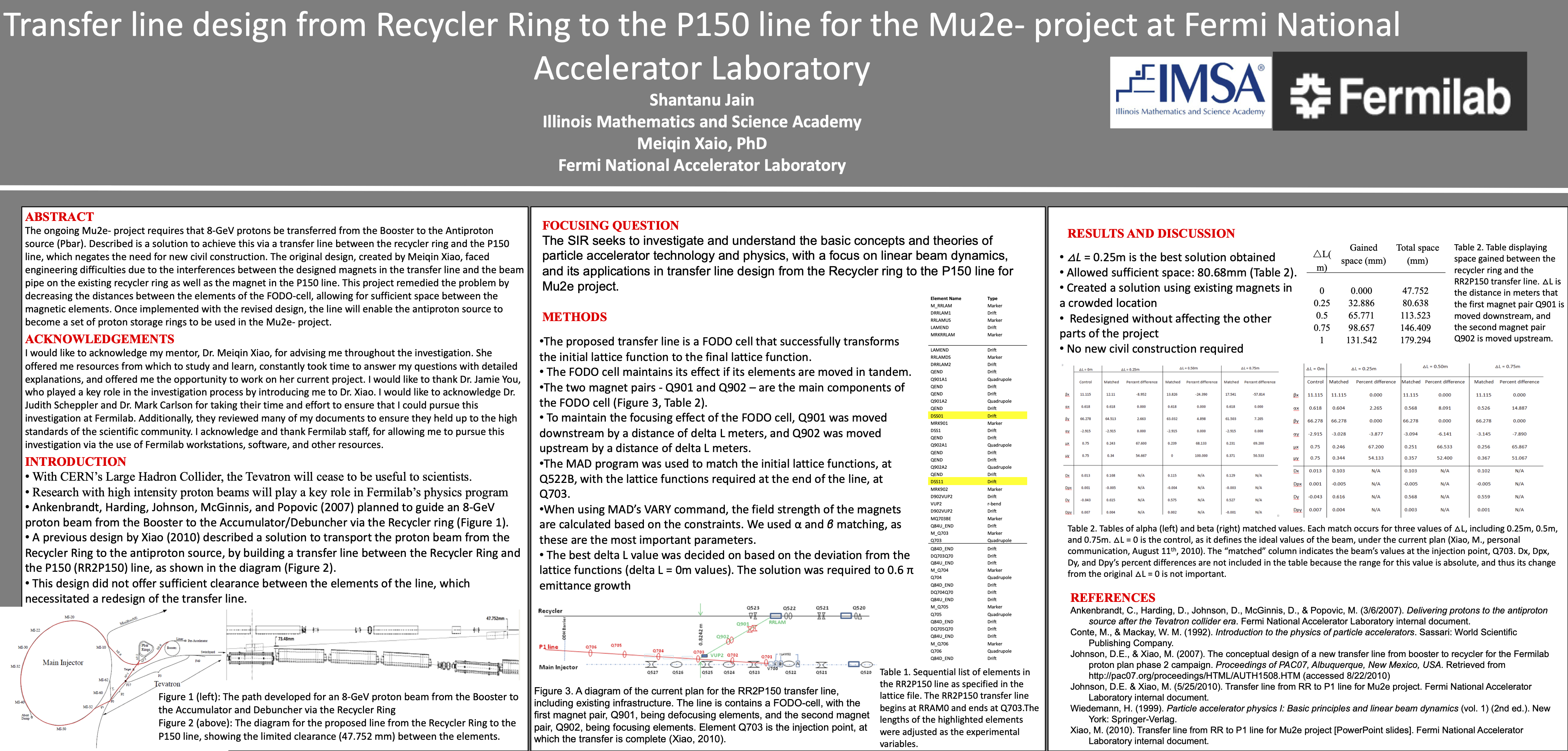

After a week, I started working on my mentor’s work on Project X. Project X was part of the larger plan to repurpose Fermilab’s infrastructure, since the LHC at CERN ended the useful life of the Tevatron as a maximum energy collider. My advisor specialized in beam line design. This means she focused not on running physics experiments, but on designing the infrastructure that is built for these experiments. In particular, the Mu2e- experiment shot muons at a target and measured the pattern and timing of the electrons that emerged from the collision. This project required that a transfer line be built between the Recycler Ring and the P150 line. Hence the name, RR2P150.

The intricate details of the project are lost on me now. But the way any particle beam is directed through a beam pipe is by applying B fields to the beam in order to change its direction. There are many types of magnet arrangements, with different numbers of magnets – 2, 4, 6, and even 8 magnets, which correct for dispersion problems of different orders. Since this was a transfer line, the beam entered with a particular set of characteristics, and to remain stable, had to output the beam with a different set of characteristics, within a given error range for each variable. The crux of my work was the layout of these magnets in the transfer line.

In order to save money, my advisor had identified several magnets that could be reused. However, the space for the placement of these magnets were also quite limited because of site constraints. So I had several sets of constraints to deal with.

To deal with this problem, I used a language called Methodical Accelerator Design (MAD)[http://mad.web.cern.ch/mad/] . It is essentially a programming language used to describe a particular beam line situation and its constraints, and then suggest possible arrangements. This was tedious, especially for a user who hardly knew how to use a terminal at the time. I once even got an email from FNAL’s computing administrator that I didn’t kill my jobs, since I just closed my terminal instead of properly killing the process.

In the end, I was able to solve the problem. My solution respected all site constraints, reused all existing magnets, and satisfied the physics design requirements. My advisor was so happy with my work that she actually included it in the paper that she published about her work that summer. All in all, it was a ton of fun and I felt quite accomplished at the end.

That summer also had crazy weather – I remember a hailstorm, rainstorms so severe that everyone left their offices early, and multiple tornado warnings. I piloted my car through all of it every day of the week. I also took 2 weeks off of my time at Fermilab to attend John’s Hopkins University Center for Talented Youth summer camp, in Berkeley, CA. That was a ton of fun, and by coincidence, I met a friend who was a year older than me and now goes to MIT as well.